II. – Latin commentaries on Arabic texts

Rhases’s division of alchemical vessels into vasa dissolutionis and vasa operationis proved unpopular in the Latin West, but his method of categorizing – which was functional rather than morphological – caught on at once. The Latin appendix in the so-called De investigatione perfectionis magisterii, for example, divides vasa into six genera, each defined by its use (Ruska, 1935a).

Under these categories the editor includes most of Rhases’s vasa operationis along with the descensory, while ignoring his blacksmithing tools. He also makes some significant additions, which are distributed as follows.

- « Vessels for the sublimation of spirits » (meaning sulfur, mercury, orpiment / realgar, and sal ammoniac) – cannina (Arabic: qinī na-flasks).

- « Vessels for the fusion of spirits » – tuba sive canna (a vessel similar to our Florence flask, and another which seems to be a retort), cannutum (vide ps. Rhases, De aluminibus et salibus,

cap. 25, in Robert Steele, 1929: here this apparatus is called a cammitum – it was a closed cylinder with an opening in the side, in which lead and mercury were sometimes coagulated), and scutellae (two pots sealed mouth to mouth, presumably for the purpose of sublimation). - « Vessels for the calcination of spirits » – vas reverberationis (a reverberatory furnace vide infra), olla (pot), and simia (a flask tapering at both ends).

- « Vessels for distillation » – distillatio per filtrum (since distillatio merely means « dripping down », the re-worker shows a pot with two cloth strips passing a solvent into two smaller pots by means of capillary action as an example of distillation: fig. 2).

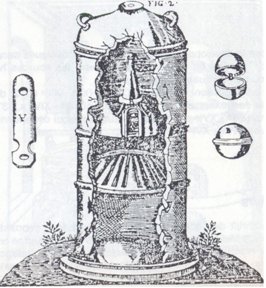

- « Vessels of congelation »- alembic duplicati (two alembics, each with its spout feeding into the other), and canna retroversa (a still whose delivery tube leads back into the cucurbit to form a refluxer: this is the « pelican » of later alchemy).

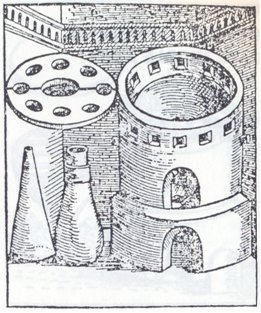

The gaps in the late medieval appendix to Rhases are as instructive as its inclusions. The treatise supplies no specific directions for making apparatus; there is no mention of dimensions, pottery techniques, or glass-blowing : the alchemist is intended to buy most of his equipment from artisans, an assumption often made by alchemical writers through the Scientific Revolution. There is no mention of water-cooling for either still-head or delivery tube, though medical writers of the 13th century knew that this reduced the loss of low boiling-point distillates (von Lippmann, 1914). Nor does the treatise know anything of fractionating methods; the use of intermediate condensing flasks between still and receiver seems to have been incorporated into alchemy during the 14th and 15th c. The Latin re-worker is also vague in his description of furnaces. The vas reverberationis (vide supra) appears to represent the medieval glass-maker’s oven. Here the fuel is segregated from the heated objects by a perforated grate : the flames pass through the grate and are driven back by an arching cover above the hearth : hence the name « reverberation furnace ». The apparent absence of open-shaft and cupellation furnaces shows that neither Rhases nor his editor were interested in large scale smelting or liquation of ores.