AN INTRODUCTION TO ALCHEMICAL APPARATUS IN THE LATE MIDDLE AGES

William NEWMAN

Universités de Harvard et de Liège

Résumé

L’auteur expose le développement des appareils alchimiques durant le moyen âge latin tardif. A cette fin il examine brièvement les sources historiques. Il groupe ces sources en quatre catégories:

1° des textes latins qui sont traduits de l’arabe (XIIe – XIIIe s.);

2° des commentaires latins sur des textes arabes (principalement XIIIe – XIVe s.);

3° des travaux originaux latins (XIIIe – XVIe s.);

4° des travaux latins qui dépendent de sources non-alchimiques (XVe – XVIe s.).

Samenvatting

De auteur beschrijft de ontwikkeling der in de alchemie gebruikte toestellen gedurende de late Middeleeuwen in het Latijnse Westen. Daartoe onderzoekt hij in het kort de historische bronnen. Hij deelt deze in vier kategorieën in:

1° Latijnse teksten die uit het Arabisch vertaald zijn (12e-13e eeuw);

2° Latijnse kommentaren op Arabische teksten (voornamelijk 13e-14e eeuw);

3° oorspronkelijke Latijnse werken (13e-16e eeuw);

4° Latijnse werken die op niet-alchemistische bronnen steunen (15e-16e eeuw).

The development of alchemical apparatus in the late Latin Middle Ages can be deduced from texts which fall within four main historical types.

- Latin texts translated from Arabic (12th-13th c.).

- Latin commentaries on Arabic texts (mainly 13th-14th c.).

- Original Latin works (13th-16th c.).

- Latin works depending on non-alchemical sources (15th- 16th c.).

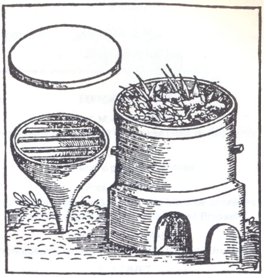

Fig. 1. – Descensory (from Holmyard, 1928).

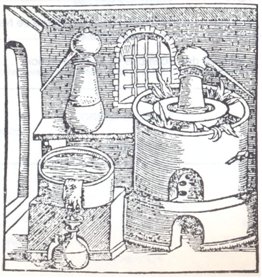

Fig. 2. – Distillation (from Holmyard, 1928)

I. – Latin texts translated from Arabic

The first period begins in earnest with the absorption of works attributed to Abū Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakarī yāar-Rāzī (d. 925), whose genuine Kitāb al-Asrār (Ruska, 1935a) was independently Latinized by two different translators, first as the L. Ebu Bacchar et Raisy, and second as the L. Rasis Ebobacre. The first of these translations was variously reworked in the 13th and 14th centuries: once with the rubric L. secretorum de voce Bubacaris (or L. Bubacaris), and in a second, appendixed version, to which the rubric De investigatione perfectionis magisterii had been added, with a false ascription to Jābir ibn Hayyān[[ This Liber de investigatione perfectionis magisterii is not the well-known work bearing the same name, also attributed to Jābir ibn Hayyān (or « Geber » in Latin), and having the incipit « Investigatione(m) hujus nobilis (sime) scientie ex continua … (TK 776). The latter text has been printed many times, beginning with the incunabulum version of the Rome printer Eucharius Silber (s.d. et l.); the former exists in manuscript only, though some parts thereof are excerpted in Ruska (1935a) = [198-237).]] . The translated part of the L. Bubacaris divides vasa [[ My rendition of Rhases’s notes on apparatus is derived entirely from Ruska (1935a) = [198-202). ]] (among which it includes furnaces and ancillary tools) into « vessels in which bodies are dissolved » (i.e. fused), and « vessels of operation, or for the treatment of species ».

The first type includes the fornax aurificum (a mis-translation of kūr, a blacksmith’s furnace), manthici (bellow), boctice (crucibles: earthenware pots made to withstand great heat), tenallia (tongs), scarpella (here probably shears), mallea (hammers), incus (anvel), and the bot et marbot (from Arabic būt-bar-būt a descensory : a perforated crucible containing reducible substances is set upon an ordinary crucible; the unit is then placed in a furnace and surrounded by coals. The contents of the upper pot will partly fuse and run into the lower one, leaving their dregs behind; if metallic oxides were to be reduced, some charcoal would be added to the upper crucible, in order to supply the necessary carbon, fig. 1). Vasa operationis include the cucurbita (a gourd-shaped vessel upon which a still-head with delivery tube rests, the whole forming a complete still; two cucurbits may be seen in fig. 2), elembic (in most texts called an « alembic », from Arabic al-anbīq, in turn derived from the Greek άμβιξ – the still-head which sits on the cucurbit, two of which may also be seen in fig. 2: « alembic » is also used in Latin to denote the complet still), cucurbitae cum elembicco caeco ( « blind alembics »: the still-head is sealed where it would normally have a delivery-tube, and then used for refluxing and sublimation), aludel (from Arabic al-uthāl, in turn from the Greek άιθάλη – a sealed sublimatory tube made from two sections; see fig. 3), cauchia (or canchia, from Greek κόγχαι – beakers), ampullae (long-necked vials), curura (Arabic : qarūra – a flask), marmor (a marble slab for trituration), moleta (here apparently a pestle, corresponding to the Arabic fihr) , fornax quae per se sufflat (Rhases’s nāfikh nafsahu – a sort of covered fire-bucket with twin bellows and a stand), mortarium de vitro (a glass mortar), and the water bath for cucurbits.